This page is considered optional for the Earlham Institute’s training course and will likely not be covered live. It is provided as additional reading material for those interested.

We discuss here how single-molecule modification data is stored in BAM files using the MM and ML tags

at the end of each line.

We are going to be building upon our knowledge of the BAM file format, so please

make sure you are familiar with it as explained in this session

where we learned about and performed sequence alignment.

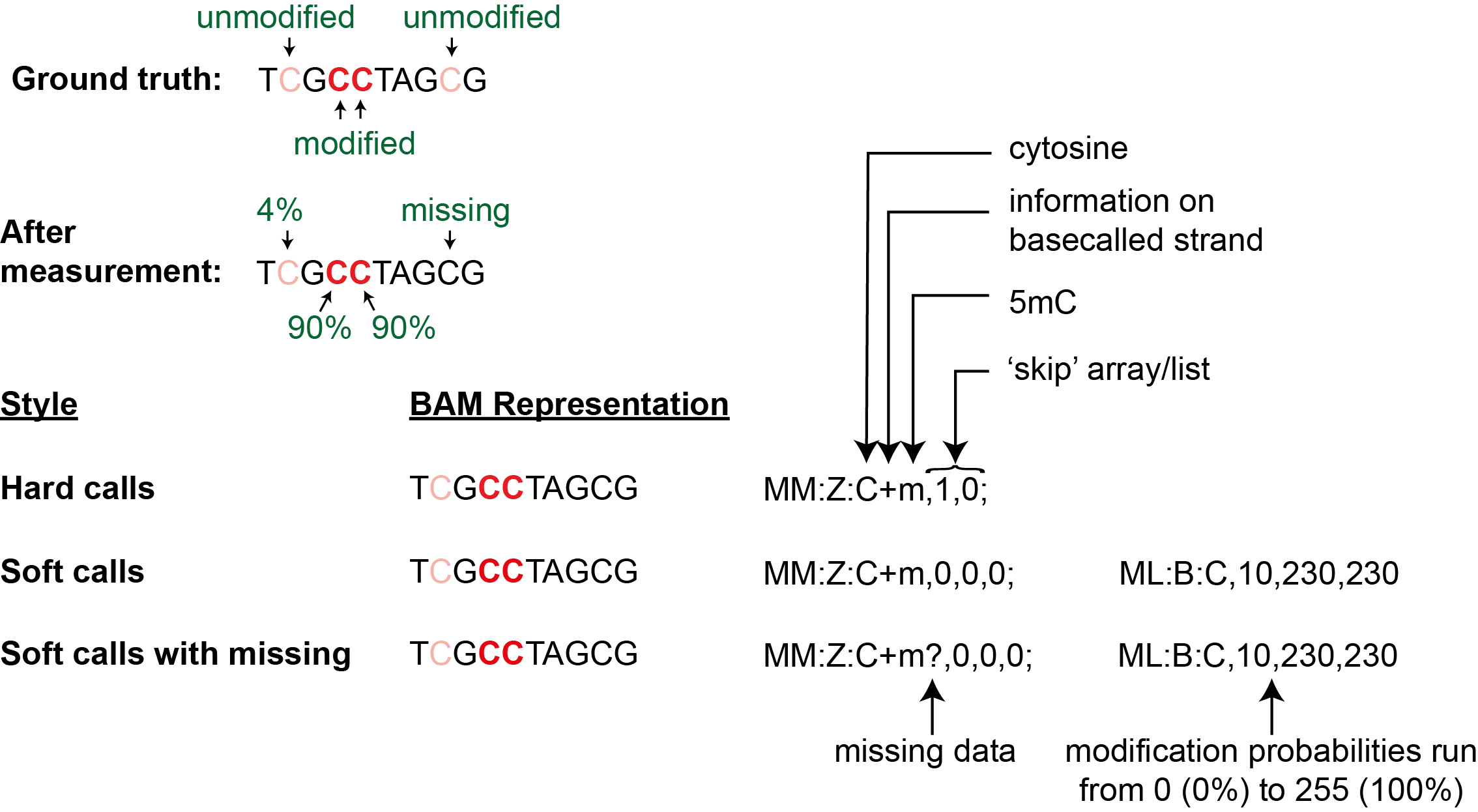

We will illustrate multiple ways to represent modification information as summarized in the figure below

using an example molecule with the sequence TCGCCTAGCG.

Let us assume the read has not been aligned to a reference genome for simplicity.

Scenario 1: Hard modification calls with no ambiguity or missing information

In the simplest scenario, we just want to mark which bases are modified and which are not per molecule. In other words, we want to store two lists: locations where bases are modified, and locations where they are not, which is essentially just one list as we know the sequence of each molecule. Although this type of mod BAM file is the simplest, tools that work with mod BAM files usually expect a probability of modification to be present as well and may throw an error if probabilities are omitted. So, we begin our discussion with this simplified format solely for pedagogical reasons.

Let us consider the example where the second and the third cytosines of the sequence of interest above have been

modified to 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and the others are unmodified.

The simplest way of storing this information is the self-explanatory list C->5mC:2,3.

For reasons we will not get into here, what is stored is instead the diff of this list i.e. instead

of storing positions of modified cytosines, we count the number of unmodified cytosines between

each successive pair of modified cytosines.

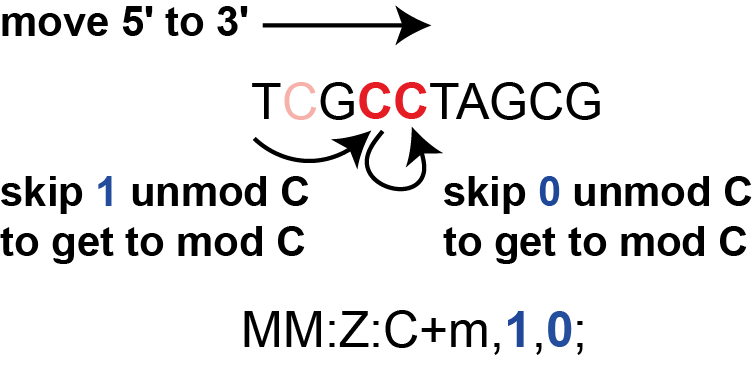

This is illustrated in the figure below.

In other words, when moving along cytosines on the sequence,

we have to skip 1 unmodified cytosine to get to the first modified cytosine and then skip 0 unmodified cytosines to get

to the second modified cytosine.

So, the modification tag reads MM:Z:C+m,1,0;.

In addition to the information that we need to execute 1 skip and 0 skips (,1,0), the tag tells

us that we are looking at cytosine modifications (C), the modification under

question is 5-methylcytosine (m), and that modification information is on the

same strand as basecalling (+). Put together, the BAM line might look like (spaces have been

replaced by tabs for simplicity):

1578e830-9886-46c8-977b-f0645dac040b 4 * 0 255 * * 0 0 TCGCCTAGCG * MM:Z:C+m,1,0;

Henceforth, we will drop the other fields in the BAM line and focus only on

the modification tags for simplicity. The first five characters of the tag

are always MM:Z:; older mod bam files may also use Mm:Z:.

Standard modifications have one letter codes or numeric codes

We have used the one-letter code m to represent 5mC in the example above.

These methylation codes are a part of the standard BAM format

specification here.

5-Hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) is represented with an h or the numeric

code 76792.

So if our example above dealt with 5hmC modification, the tag would

read as MM:Z:C+h,1,0; or MM:Z:C+76792,1,0;.

If this sample molecule were a part of our yeast dataset where thymidines are substituted by

BrdUs (numeric code 472252), the tag would read MM:Z:T+472552,0; if we wanted

to record that the first thymidine in our sample sequence TCGCCTAGCG was substituted.

As older modification tools did not recognize numeric codes,

we have represented BrdU substitution using the ambiguous one letter code T

instead i.e. MM:Z:T+T,0;.

Bases where calls are missing are considered unmodified

In our example above, we did not talk about the fourth cytosine at all. The ground truth is that information about its modification status is missing. But in this ‘hard call’ representation, ‘missing’ is equivalent to ‘unmodified’.

(optional) Multiple types of modifications are present

Let us consider the scenario where both 5mC and 5hmC modifications are present in the sample sequence TCGCCTAGCG.

The tag might read (a space has been replaced by a tab for simplicity) MM:Z:C+m,1,0; MM:Z:C+h,3;.

The interpretation is that the second and third cytosines (execute one skip and zero skips) have been modified to 5mC and

the fourth (execute three skips) has been modified to 5hmC.

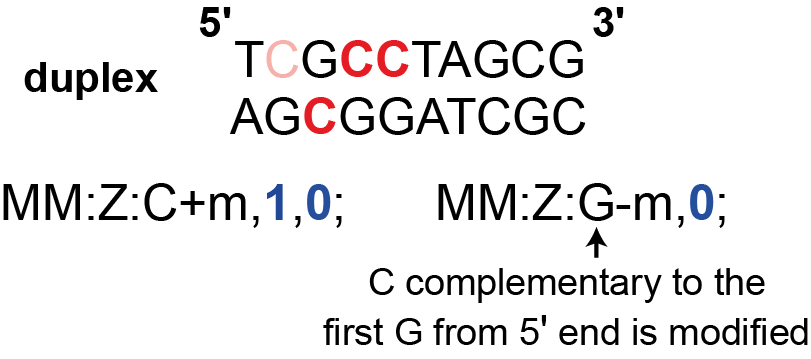

(optional) Modifications are present on the basecalled strand and its complement

ONT have released a ‘duplex’ method where both a strand and its complement from the same cell are sequenced.

So, one can obtain modification status on both a strand and its complement.

In our sample sequence TCGCCTAGCG, let’s say the second and third cytosines have been modified to 5mC,

and the first cytosine on the complementary strand AGCGGATCGC has been modified to 5mC.

The tag would then read (replace spaces with tabs) MM:Z:C+m,1,0; MM:Z:G-m,0;.

Scenario 2: Soft modification calls with probabilities

We dealt with a ‘binary’ mod BAM file in the previous section. Here, we look at a common

format with a probability of modification per base typically output by modification callers.

So, we need to store both a base coordinate and a number between 0 and 1 per coordinate.

For base coordinates, we just use the ‘skip’ representation from the previous section.

For probabilities, we convert them from a floating point number in the 0-1 range to an integer

in the 0-255 range and store them using a second tag that begins with ML:B:C.

Let us revisit the sample sequence TCGCCTAGCG.

Let us say the ground truth is that the probabilities of methylation of each cytosine are

given by the table below.

position modification_probability

1 0.04

2 0.90

3 0.90

As you can see, the modification status of the fourth cytosine is missing.

Preparing the base coordinate array (or list)

We prepare the base coordinate array like in the previous example.

Since we have data at all cytosines except the last, the tag reads MM:Z:C+m,0,0,0;

i.e. all skips are zero as we have data at every cytosine except the last.

If we want to mark the missing cytosine as unmodified, we use the tag as is,

or we add an optional period . after the modification code MM:Z:C+m.,0,0,0;.

If we want to mark the missing cytosine as missing, we use a question mark ?

instead, to form MM:Z:C+m?,0,0,0;

Preparing the modification probability array (or list)

We prepare the probability array by converting the floating point numbers to an

integer between 0 - 255. We first note that 0.04 is between 10/256 and 11/256.

Similarly, 0.90 is between 230/256 and 231/256.

Thus, the probability array reads ML:B:C,10,230,230.

Concatenating the two strings

Concatenating the two tags with a tab (represented as a space below), we get one of three possible strings.

MM:Z:C+m,0,0,0; ML:B:C,10,230,230MM:Z:C+m.,0,0,0; ML:B:C,10,230,230MM:Z:C+m?,0,0,0; ML:B:C,10,230,230

The first two strings ask us to treat missing cytosines as unmodified, whereas the last line asks us to treat the missing cytosine as missing.

Introduction to manipulation of mod BAM file

Several tools use mod BAM files as input (samtools, modkit, IGV, modbamtools)

and produce images or tab-separated files as output.

We will be using these programs throughout the course.

These output files are typically easier to read and understand than the

raw mod BAM file.

As the modification field is still developing, there may not be a tool that does exactly what you want. Knowing how a BAM file is structured could help you if you have to write the tool yourself.

Convert BAM files to TSV

The simplest operation is conversion of BAM files to tab-separated values format.

A table like the following is much easier to digest than a string like

MM:Z:C+m.,0,0,0; ML:B:C,10,230,230.

position modification_probability

1 0.04

2 0.90

3 0.90

One can use modkit extract to perform the conversion.

The command syntax is modkit extract [OPTIONS] <IN_BAM> <OUT_PATH>.

We have already encountered this command in the

session on modification detection.

Example discussion on how to write a tool yourself

Let’s say you want a tool to produce a table with read ids and modification counts per read. An example is shown below

read_id mod_count read_length

f48c6a85-db3c-445f-865b-4bb876bd4a18 100 1000

5ddb8919-89de-4ffd-b052-423e53cff109 2000 100000

Such a tool does not exist to the best of our knowledge, but one can orchestrate pre-existing tools using a scripting language to achieve this. The following ideas could work:

- you need to get a table with read_id, modification_probability columns using

modkit extractand process the table using, say, a python or an R script. - you can read the mod BAM file directly with python using a library like

pysam - you can convert the mod BAM file to plain text (.sam) with

samtoolsand process the text with python/R.

For options 2 and 3, you will need to know how a BAM file is structured, so the knowledge from this session comes in handy. For option 1, you need not know much about a BAM file.

Problems with historical mod BAM files

Caution: historical mod BAM files were not well-written

Historically, researchers did not use the ? or . notations or one-letter modification

codes correctly.

In other words, questions like ‘are missing bases unmodified or missing?’,

‘what base is modified?’ may not be straightforward to answer and you may need to inspect

the BAM files yourself using the materials learned in this session.